Removing the solid fraction of slurry and returning the liquid to the lagoon has long been a common practice on the continent, but there now appears a determined push to popularise it in Ireland.

There are many advantages to removing the fibre from slurry, not least of which is that, in effect, it can increase on-farm storage capacity by around 30%, or even more if pressed out to a higher dry matter (DM).

Catching up with the continentals

Despite Ireland’s lead in the mechanisation of slurry distribution with a plethora of forward-looking tanker manufacturers, slurry separation is a market dominated by continental manufacturers, of which one of the leaders is Vogelsang of Germany.

Vogelsang is a name best known for its macerators which are fitted to many Irish-built tankers, although the company does not actually use the term in its literature, referring to them as distributors instead.

These items are now meeting stiff competition from homegrown products, but when it comes to fully integrated slurry pumping and separation technology, the German company is still well ahead.

XSplit on show

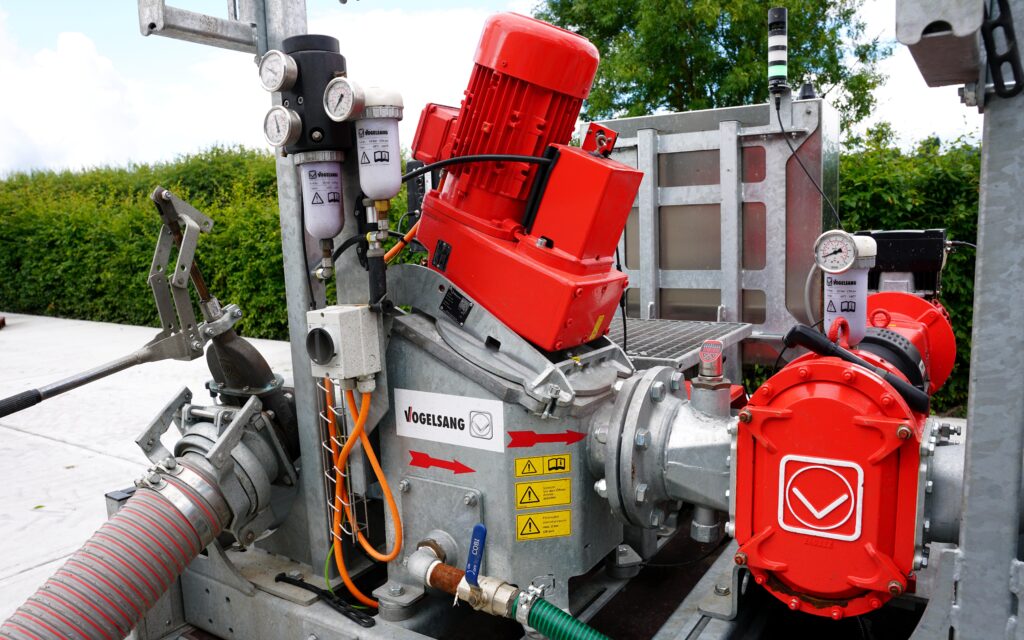

Vogelsang has taken to the road this summer to demonstrate its range of products with a specially built demo unit which is fitted out with an XSplit separator and the various pumps and cutters (macerators) that may be used in conjunction with it.

Its latest visit was to a farm run by one of the company’s technical consultants here in Ireland, David Whelehan of Mullingar, Co. Westmeath.

David runs a beef enterprise housed on slats and the unit was put to work emptying one tank, separating the solids into a dump trailer and discharging the liquid back into a second tank.

For this situation, and indeed most situations on Irish stock farms, the hardware present was something of an overkill, and not all the individual items will be required, but it clearly demonstrated just how well a properly planned system can work.

The process

The first item on the trailer is a fill pump which draws the slurry from the tank and through a RotaCut macerator, the chamber of which allows any stones to settle out of the flow.

This then passes the now homogenous liquid to an elevator pump which lifts it up to the XSplit separator.

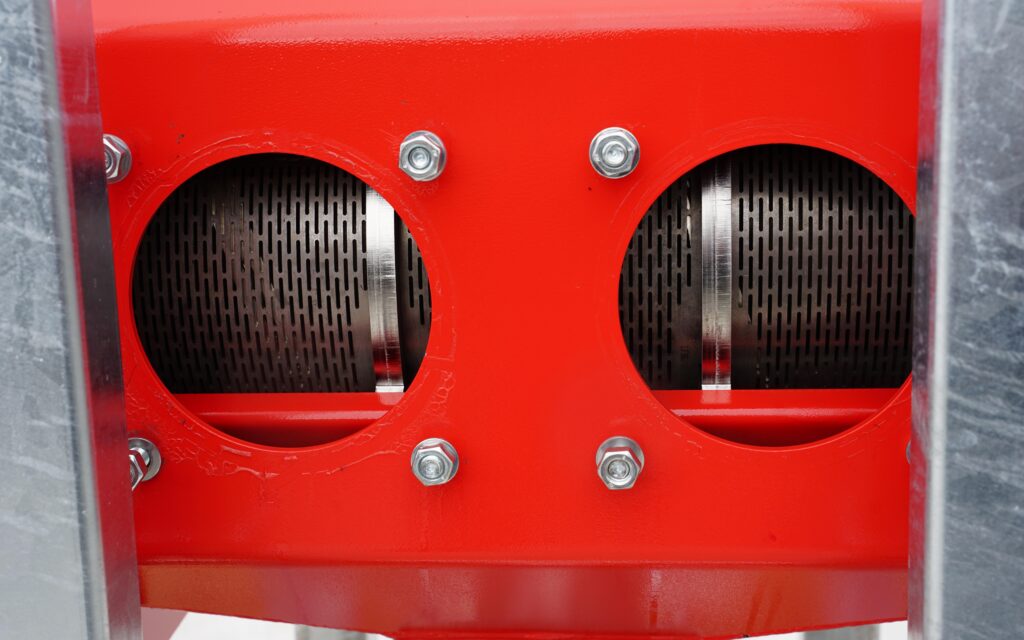

It is here that the real work is done with a screw forcing the liquid against a screen resulting in the fluid faction being squeezed out and down a discharge pipe.

The fibrous solids being pushed out of the end of the separation cylinder, falling into a trailer below.

The design of the XSplit is such that the slurry is not pressed against the drive shaft seal, instead, it exits from a gap between the separating cylinder and the motor, reducing maintenance costs.

Gravity discharge of the liquid will often be quite sufficient in most situations, but if it needs to be moved to a more distant tank or lagoon, a third pump can be installed to move it away from the separator.

On the demo unit it runs off the same shaft as the lift pump.

XSplit automation

All the pumps are the company’s own rotary lobe pumps of suitable capacity, and all are powered by a three-phase electrical supply, provided on the day by a hired-in generator.

This particular set up is designed with a maximum capacity of 50m³/hr, but David recommends that it is best operated at around 30-40m³/hr, reducing stress on components and demands on the motors.

Having automatic control, it can be quite happily left operating on its own with various safety sensors and switches being able to close it down if things go wrong.

Pricing an installation is very much dependent on a host of variables so the company is reluctant to put a figure on it, but it would probably be fair to say that the cost of a basic installation, with three-phase already at hand, would come in at the price of a reasonable second-hand tractor.

Power requirements

It is this element of the set up which might be an issue for many farms that are still reliant on a single-phase supply, a power source that is just not up to the demands of the various motors involved, especially that which drives the XSplit itself.

Connection to a three-phase supply is expensive, yet the majority of farms will have a back-up generator, so if this were capable of a 415V output then it can be used to power the installation, which would only need to be run on an occasional basis.

The growth in farm size and the push to electrify everything may see a three-phase connection being considered a necessary investment for many anyway, just so long as the local grid can handle the demand.

Alternatively, there is a great deal of interest from contractors who see a mobile system as a natural extension to their slurry spreading services.

Trailed units, or units on skids, complete with generator, being the favoured option.

Slurry as a product

While a separator may allow more slurry to be stored, the advantages don’t stop there. The liquid becomes a more consistent product and easier to spread, immediately soaking into the ground without any residue.

The solid can be added to the muck heap, although the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine (DAFM) still classifies it as slurry, albeit very concentrated one with a DM of around 30-40%, so run-off from a storage area has to be collected and spread.

It might also be used for green bedding, a practice that is common elsewhere and appears to be a perfectly healthy option, even for dairy herds, but consumer resistance may not encourage its adoption in Ireland.