The weeks of spring are a critical period for farms in Ireland aiming to get cows back in calf quickly to ensure a compact-calving interval.

Teagasc research shows nationally only 58% of the dairy herd calves in the first six weeks of the calving season and a calving interval of 394 days.

The Teagasc targets are 80% calved in the first six weeks and a calving interval of 365 days. Subclinical mineral deficiency may be adversely affecting reproductive performance in Irish herds and addressing this issue could improve reproductive performance nationally.

Years of research has documented how trace mineral nutrition is vital for reproductive performance in cattle and cattle that are in poor mineral status may have poorer fertility.

Zinc-deficient cows appear to display abnormal oestrus as well as experience a decrease in fertility (Underwood, 1981).

A deficiency in copper (Cu) can lead to decreased conception rates, infertility, silent heats and foetal resorption (Hostetler et al., 2003).

A deficiency in selenium (Se) can lead to cystic ovaries and erratic, weak, or silent heat periods (Hostetler et al., 2003).

Manganese (Mn) deficiency will result in impaired ovulation (Wilson, 1952). While clinical deficiency in cattle will display the tell-tale clinical signs of deficiency, like the brittle coat of a copper (Cu) deficient animal, the key is the unseen issue of subclinical deficiency.

Click here, complete form and get a free consultation from Virbac on the benefits of injectable trace mineral top up.

Understanding subclinical disease

Subclinical disease is defined as an illness that is staying below the surface of clinical detection, meaning there are no recognisable signs, but the disease can still be adversely affecting the animal.

Marginal or subclinical mineral deficiency in cattle will not show clinical signs that will help with diagnosis, but the effects of subclinical deficiency may still adversely affect herds’ reproductive and disease status, so cows may appear healthy but they may not be achieving or maintaining pregnancy.

How can subclinical mineral deficiency occur?

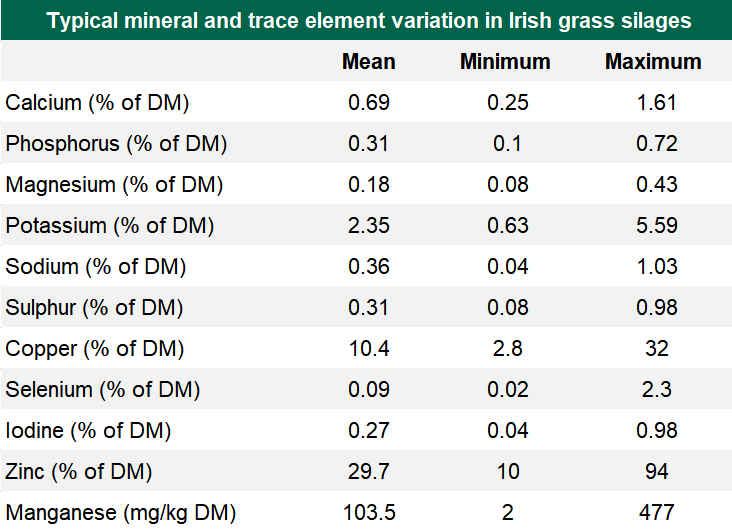

In Ireland, herd cases of trace mineral deficiency arise frequently but are often not reported. It was reported by Rogers and Murphy (2000), that within Irish grass silages, 63% are low in copper (Cu), 69% are very low in selenium (Se) and 29% are low in zinc (Zn) – (see table below).

This means a lot of cattle are on the threshold of subclinical deficiency as they are not offered silage with adequate minerals.

Furthermore, even cattle fed on grass silage or forages that are meeting mineral requirements simply may not eat an adequate level of forage to maintain mineral levels.

In the pre-calving period, dry matter intake (DMI) falls by 30-35%, meaning cows may need to use their mineral stores like (e.g. in the liver) pre and post-calving for maintenance.

Unfortunately, during this period there can be increase an excretion of minerals which can be made worse by stress, but there is also a massive increase in demand for minerals.

In the weeks coming up to calving, the unborn calf will be growing rapidly and its only supply of minerals will be across the placenta from the dam.

After calving, the cow will be lactating, recovering from calving and trying to get back in calf. All these processes mean there is a huge spike in mineral demand, while intake is reduced, meaning mineral stores of cows can become depleted.

This is how even seemingly well-fed cows and herds can fall into subclinical mineral deficiency and fail to achieve or maintain pregnancy.

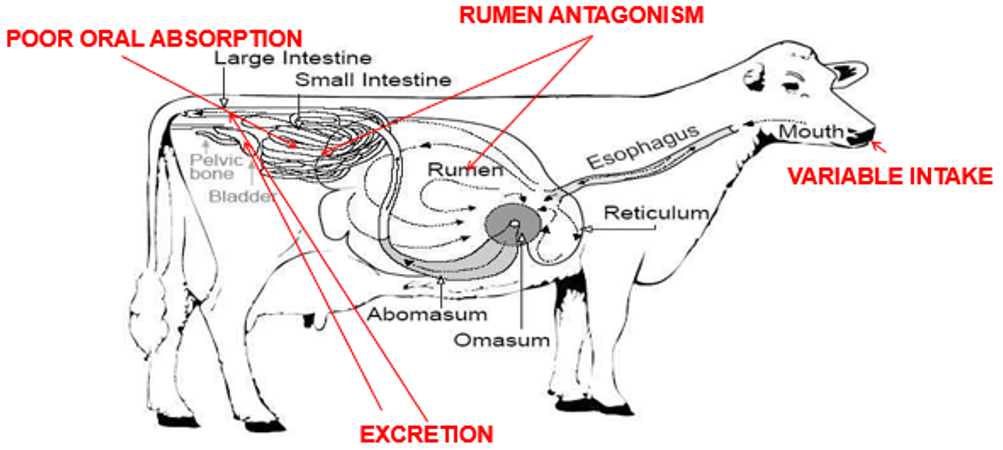

Other issues complicate the situation further at this time. Oral minerals, depending on their form, are relatively poorly absorbed by cattle.

Only 1-5% of oral copper is absorbed by adult cattle, for zinc (Zn) 10-20% and manganese (Mn) is only absorbed about 1%. Thus, even using silage that has adequate minerals, oral trace mineral supplementation can take weeks-to-months to build back up the mineral store in cattle.

Rumen antagonism further hampers the poor oral mineral absorption. Antagonists are minerals like sulphur (S), calcium (Ca), iron (Fe) and molybdenum (Mo), that despite being essential parts of the bovine diet, when supplied above certain levels, they adversely affect the absorption of other minerals like copper (Cu), zinc (Zn) or selenium (Se).

This means that even though diets appear to have adequate levels of trace minerals, may not be effective in maintaining cows’ mineral levels, as the antagonists are blocking the minerals being absorbed.

Click here, complete form and get a free consultation from Virbac on the benefits of injectable trace mineral top up.

How to prevent subclinical deficiency at pre-breeding?

Strategic Trace Mineral Injections are a fast and effective way for farmers to enhance their cows mineral status in the pre-breeding window.

Strategic Trace Mineral Injections are a popular way to improved herd performance in the US, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand.

Strategic Trace Mineral Injection could help to improve the overall pregnancy rate and calving distribution.

Years of research from leading animal health and veterinary universities from around the world have demonstrated the potential benefits of this strategic mineral injections.

Strategic Trace Mineral Injections bypass the harsh rumen environment and antagonists, rapidly raise circulating mineral levels in cows within 8-to-10 hours, and after 24 hours, the key minerals are at raised concentrations in the vital storage organs like the liver (Pogge et al., 2012).

From here the minerals can be incorporated into the different body systems to help maintain immunity, fertility and performance.

Teagasc estimate that a cow calving in May will generate €400 less profit than a cow calving in February, due to higher feed costs and reduced yield and, for every 100 cows, compact calving is worth – on average – €10,000-12,000 (€100-120/cow/year).

Pre-breeding supplementation helps to raise not only the trace minerals, but also the essential enzyme levels in cows rapidly and effectively, which could drastically assist farmers to get cows and heifers back in calf in a tighter-calving pattern.

Several studies from leading US universities have researched the potential benefits of injectable trace mineral supplementation in cows in the pre-breeding period, with improvements in overall pregnancy and improved calving distribution (Mundell et al, 2012).

Ask your vet how an injectable trace mineral supplement could help get your cows back in calf.

More information

Click here, complete form and get a free consultation from Virbac on the benefits of injectable trace mineral top up.

References:

- Teagasc Breeding Management https://www.teagasc.ie/animals/dairy/breeding–genetics/breeding-management/

- Underwood, E.J. (1981) The Mineral Nutrition of Livestock. 2nd Edition, Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux, Slough.

- Wilson, J. G. 1952. Herd functional infertility, with reference to nutrition and mineral intake. Vet. Rec. 64:621–623.

- Hostetler CE, Kincaid RL, Mirando MA., Vet J. 2003 Sep;166(2):125-39. The role of essential trace elements in embryonic and fetal development in livestock.

- Rogers, P.A.M. and Murphy, R. (2000) Levels of Dry Matter, Major Elements (calcium, magnesium, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, sodium and sulphur) and Trace Elements (cobalt, copper, iodine, manganese, molybdenum, selenium and zinc) in Irish Grass, Silage and Hay http://homepage.eircom.net/~progers/0forage.htm

- Dry and transition cow nutrition for the grazing Irish dairy herd, Dr Finbar Mulligan and Catherine Carty MVB https://ihfa.ie/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Grassland-Association-paper-Jan-2016-Finbar-Mulligan.pdf

- Pogge, D. & Richter, E. Mineral concentrations of plasma and liver following injection with a trace mineral complex differ among Angus and Simmental cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 90, 2692–2698 (2012).

- Effects of prepartum and postpartum bolus injections of trace minerals on performance of beef cows and calves grazing native range 2012 L. R. Mundell, J. R. Jaeger, J. W. Waggoner, J. S. Stevenson, D. M. Grieger, L. A. Pacheco, J. W. Bolte, N. A. Aubel, G. J. Eckerle, M. J. Macek, S. M. Ensley, L. J. Havenga, and K. C. Olson